Last week it was time once again for the Frieze Art Fair, London’s annual, thoroughly exhausting week-long art-viewing marathon. Everywhere I went I felt the presence of the 10,000-pound elephant in the room: the art market could be felt in every aspect of what was happening in London. There was more art for sale than I could ever imagine, and though I worked hard to see the entire smorgasbord of gallery and museum shows, no one person could possibly fit it all in. There was also a second art fair, the Pavilion of Art and Design (PAD) for an audience in search of more mature, and historical work. (Both these fairs will pop up soon in New York—PAD next month and Frieze next May—so don’t fret, there will be plenty of fairs for everyone.) And then there were evening and day sale auctions aplenty, including the usual Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips as well as newcomer Bonhams Contemporary (headed by the lovely Benedetta Ghione).

There were a few worthwhile gallery shows to see, including Pilar Ordovas’s inaugural show “Bacon and Rembrandt,” which proved to me that you can put Bacon on just about anything and it’s guaranteed to be good. But the big whopper spectacle of the week was the launch of a third London space for White Cube gallery, this one in London’s Bermondsey district. With over 40,000 square feet of brand new exhibition space, it left my head spinning just trying to imagine whether there could ever be enough clients and enough art to justify such a leviathan. The threat of a humungus new Damien Hirst show is what came to mind, and I only hope for his collectors’ sake that he doesn’t do another one like the Sotheby’s barnsale of September 2008, though a newly minted Damien Hirst is still far better than most things offered in London last week.

So what was in the new White Cube, you wonder? A few project spaces with some unremarkable mini shows, and a huge room with a group show of some average works by market-friendly names. Behind closed doors there were multiple private sales rooms filled with sundry pieces by artists on the gallery’s roster, and in back there was also a screening room where a short film by former YBA (Young British Artist) veterans Jake and Dinos Chapman was playing. In the film a drugged-out prostitute was being covered in paint by her john, with all of this shot from the point of view of a cockroach. It was a new low-point for an artist duo that once was once fresh and promising but now looks insular and stale. Face it, the YBAs happened over 15 years ago, so that historic membership card has long since expired.

While all of this art went up for sale around town, the global financial crisis raged throughout Europe, so collectors were understandably feeling a bit shaky. Nonetheless the art selling machine didn’t hesitate to churn out more product than ever before, with the Pace and Zwirner galleries still threatening to open brand new London mega branches. Perhaps that’s the message of White Cube’s uber-jet-set honcho Jay Jopling’s 40,000 square feet: “No more New York galleries in my town.” But I can’t imagine who will buy all this stuff and where they will put it.

Of course, a large part of the skill in collecting contemporary art is in having the confidence to believe that you are able to weed out the 99 percent of art that won’t survive the decade. I’m fascinated by the “more the merrier” phenomenon, however I can’t help but fear what may happen if one day these eager-beaver collectors wake up and realize that they’ve been overstuffed by an art economy that’s overpriced and underperforming. If that happens it will be bad for everyone—the dealers, the auction houses and even dedicated art buyers like myself. So I can only hope that the current art glut isn’t the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

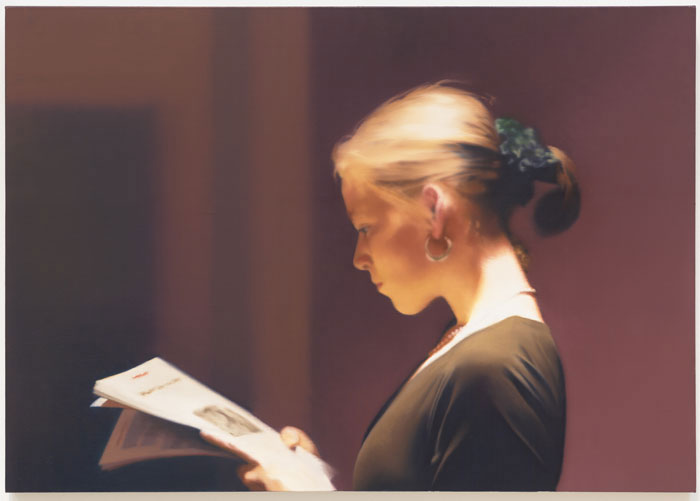

Two of the artists who were showcased this week in London unknowingly echoed one another in maligning collectors and the market, yet they have both been fed from the very hand they were biting. Seventy-nine year old Gerhard Richter is arguably the greatest living painter in the world, and is the subject of a major retrospective at London’s Tate Modern titled “Panorama.” While some found the exhibition overhung, and though the lighting was definitely too dark, the show was a revelation to me, and several times it gave me shivers.

In an interview, Mr. Richter once said that Marcel Duchamp had “killed painting,” and that in response he had dedicated his own lifetime to trying to resurrect it. And resurrect it he did by painting photography-based figurative works with creepy WWII German imagery like his Nazi uniformed uncle Rudi, and the Allies’ methodical bombing of Cologne. A roomful of paintings of the tragic government authorized murders of the Baader Meinhof terrorist gang weren’t my personal favorites, but they certainly are haunting. Mr. Richter has always alternated between this dark and disturbing photography-based practice and abstract paintings made with sponges with which he “squeegees” paint in exquisite colors across the layered canvas. (Some of these have sold for over $10 million.) Seeing the exhibition, I understood for the first time this counterpart to his figurative work—how the beautiful color abstractions serve as a kind of therapy for someone buried in his own nightmares and the weight of art history. The show successfully alternated between the two styles in a way that made me understand how he kept his sanity while suffering from such haunting memories.

But in a rare press conference he gave before this show he said, referring to the $10-14 million pre-sale estimate on his 1982 candle painting, Kerze (Candle) which was to be auctioned at Christie’s during Frieze week, “it’s just as absurd as the banking crisis.” He then added, “it’s impossible to understand and it’s daft.” Regarding the art market, he managed to throw it, too, a solid undercut by saying that though the market had changed in the last few years, “it became worse.” Strong words from a man who shows at the famous Marian Goodman Gallery where collectors line up for his work, and pay over a million dollars a painting. If an artist doesn’t like his prices, I would suggest he fix the situation by lowering them, or by giving his work to public institutions so that the precious canvases no longer have to serve the whims of the haute bourgeoisie.

In short, I don’t agree with Mr. Richter. His work is fantastic, and so it’s well worth whatever someone can afford to pay for it. Frankly I only wish I could live with a few of those beautiful works in my own living room.

A few weeks ago, in an article in the New Yorker, Jacob Kassay, the young artist whose work has been setting shockingly high prices at auction recently with his silver paintings, said, “all collectors have is money.” I find that somewhat insulting, coming from a 27 year old painter, one who only hit our radar screen because his works shot from $10,000 to a $250,000 in under a year. I caught up with him this week in London, where he had been granted a full show at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA); quite an honor for a kid London had almost never seen, or even heard of.

The show was worth seeing because, contrary to the critical view that he is simply copying Swiss conceptual artist Rudolfs Stingel, Mr. Kassay instead spoke, in a lecture, about his references to the under-appreciated minimalist painter Jo Baer as well as the venerable Ellsworth Kelly. The good looking and well spoken young man expressed his interest in light and reflectivity as well as perception, dimension and space. If he succeeds in forging a career, he will join a new generation of artists who are revisiting Minimalism; if not, he’ll be a glowing silver flash in the pan, but one we’ll not soon forget.

I myself haven’t made up my mind about him. I would prefer to wait to see, and give him time, but the hype and the hoopla are definitely big-time fun. I managed to throw a dart at him during his talk by asking him if he had been misquoted with respect to “collector’s money,” to which he answered that he stood by his statement because he needed to protect himself from issues of money and the market in order to focus on his practice. It’s a refrain we’ve heard before, and it sounds nice if you’re willing to pretend you’ve forgotten that the only reason everyone’s talking about you is because you’re a twenty-to-one winner on the auction block.

Between dealers and auction houses that are flooding the market, and artists who complain that their auction prices are too high while they indirectly benefit from them, how can I help but wonder how people who live in glass houses manage to throw so many stones? In fact, Richter has even used panes of glass to make sculptures that refer to the visual blurring of perception, all referencing, of course, Marcel Duchamp’s famous Large Glass. I found them interesting but unconvincing; he’s just not a good sculptor. And while I don’t care for Kassay’s moaning about all the auction interest the world has heaped on him, I thought his installation of silver paintings at the ICA was original and even promising.

With so much trouble in the world, and people protesting the financial crisis in Greece, and dictatorships in the Middle East, and when there’s even a fascinating and worthy Occupy Wall Street movement germinating in our own city, it’s easy to see why artists would shake their heads in disapproval at escalating art prices; most of the world doesn’t have adequate health care or enough food to eat, including too many in our own country. But that knee-jerk view is too facile, because all the money spent on art the world over in an entire year wouldn’t make even a small dent in any of these macro problems. I am in favor of helping people in need, but not at the expense of culture; I’m not a moralist.

We’d all feel better if the artists produced less, the galleries sold less, the museums did fewer and better shows and the collectors bought less of it for a while—at least until the world settles down a bit. Everyone in the art world has enjoyed the benefits of the monetary appreciation of art, so I don’t have much patience for those who complain about it. Perhaps what Richter really meant is that his art is worth more than everyone else’s, in which case I agree with him. But I’m not offended by what someone can afford to pay for a Richter, I’m just jealous.

The week’s visit confirmed that more is not always more. I came away with the distinct feeling that things weren’t always selling all that easily, neither in the fairs nor in the galleries, in part because collectors are offered far too many options. Speaking of options, next week Paris has its own annual art fair, the FIAC, held in the majestic Grand Palais, and many of the galleries in London’s Frieze move on to Paris for more of the same in a different locale. As for Mr. Richter’s candle painting this past Friday night at Christie’s, he will be very disappointed to find out that it sold for $16.5 million, more than 15 percent over its high pre-sale estimate and a new world record for his work at auction. And what of Mr. Kassay you say? Well, his two pictures made almost a quarter of a million dollars each, another strong showing. London remains a boomtown for art, and the invisible elephant is still charging ahead…for now.