from MODERN, Spring 2011

COLLECTOR AND AUTHOR ADAM LINDEMANN DESCRIBES HIS FORAY INTO DESIGN, AND COMMENTS ON THE STATE OF THE MARKET

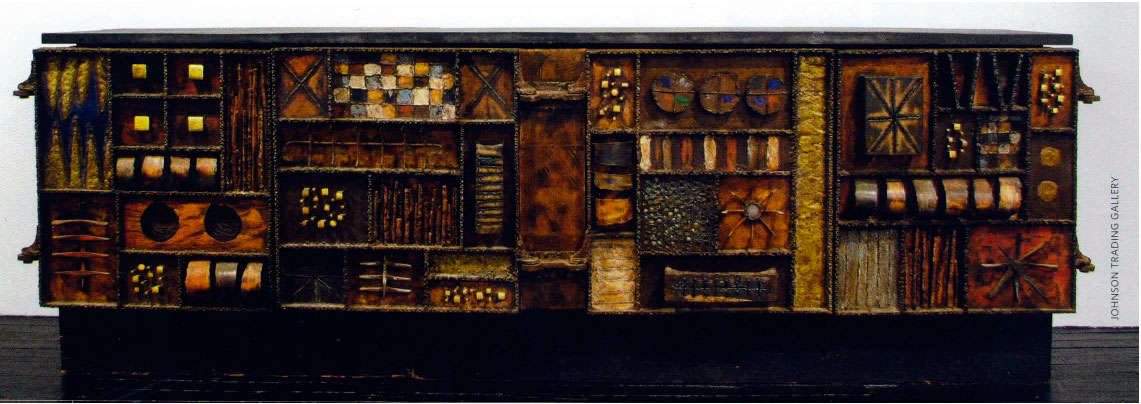

I BUMPED INTO COLLECTING DESIGN in a rather unglamorous way. I was shopping in the vintage furnishings section of the Manhattan store ABC Carpet & Home about eight years ago when I came across mirror-fronted furniture by the 1970s designer Paul Evans. It was really crazy stuff that reminded me of a cross between the sets in the film A Clockwork Orange and a Klingon spaceship in my favorite TV show, Star Trek. My fiancée hated every bit of it, but indulged my enthusiasm as I asked the young man in the booth, Paul Johnson, to sell me a houseful of Evans’s work. This he did. The trove included a massive sculpted-front buffet, as well as pieces in Evans’s perforated, faceted, and “Argente” styles. I literally bought everything. A short time later, when Evans works began to appear in major auctions and were bought by European dealers and collectors, I felt like I had hit a small jackpot. That only led me to buy more design, both vintage and contemporary. But I hadn’t really understood what I had gotten myself into.

Before my Evans moment, I focused on contemporary art. But after spending a few hundred hours with dealers, collectors, interior designers, and auction house experts, I developed a new way of looking at and living with furniture, and gained an understanding of how art differs from design. The art world likes to think it has ownership of the things of the highest intellectual content as well as economic value. Yet design has shaped our world in a much more tangible way, and an understanding of objects and what they mean is still developing. As a category, design is still undervalued, and perhaps always will be. The “decorative arts” are, vexingly, second-class citizens compared to the “fine arts.” One thing I learned is how much senseless confusion has been created around the question of what is art and what is design. Art is art, and furniture is furniture. Designers are not artists, and artists are not designers. The very concept of limited edition “design/art” is merely a marketing tactic to get hefty art-level prices for works of design. The ploy seemed to work for a while, but has now, I think, run its course.

The recent release of my book Collecting Design came at the end of a global financial crisis—a sensitive time for the design collecting field. Art prices rebounded strongly on reduced volumes, but can we say the same about the design market? Examples of contemporary design that were bid up to five or ten times their original value at auction are now struggling to find bidders. But if value is set aside for a moment, the stretch from 2000 to 2010 did change the furniture market forever. Names like Carlo Mollino, Eileen Gray, Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, Paul Dupré-Lafon, and Jean-Michel Frank now provoke excitement. These are early days, and many fields are yet to be rediscovered. There’s percolating interest in Italian radical design; I’m partial to French design of the 1960s. Design collecting has a real future, but when most people still think “design” means mass-produced plastic stacking chairs, we still have a long way to go.